Communication Models to Modern Transactional Processes

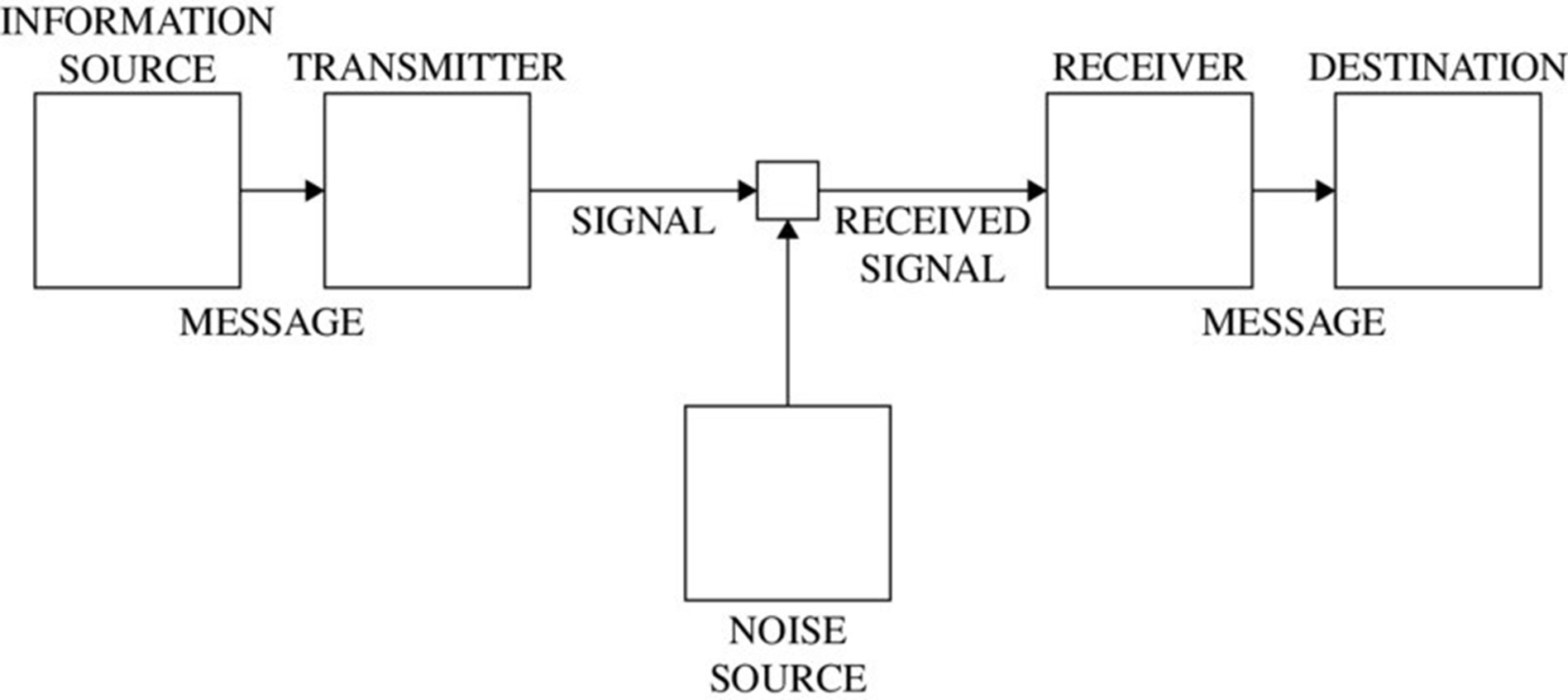

Theoretically, our understanding of communication models has gone through great transformations over the past 100 years. This suggests that these transformations and trends are a guide for emerging communication contexts, specifically those in the digital and social age. The 1947 Shannon–Weaver model of communication is used as the foundation for much of our knowledge of communication today. It highlights many important takeaways for effective communication. The model identifies eight concepts as key elements for information transfer: source, encoder, message, channel, decoder, receiver, noise, and feedback.

In this model, shared meaning is imperative for effective communication. Most importantly, it provides an explanation for miscommunication. The receiver of a message could walk away without the intended message not only due to external noise, but also due to the encoding and decoding process. This applies to social media conversations as well. For example, a friend may write a message on your Facebook wall. Your friend knows that the wall is a public space where others are likely to see the message. She wishes to be discreet about the meaning of her message, so she uses personal jokes and acronyms in her message, rather than being forthcoming. The message is so secretive that even you, the intended receiver, don’t understand the meaning of the message. In this example, there was no external noise to cause the miscommunication; the technology worked appropriately and there was no language barrier between sender and receiver. However, the encoding and decoding process did not align, thus resulting in miscommunication. This is one of the first models of communication that included an explanation for why miscommunication occurs even without external noise. Regardless of the foundational importance of the Shannon–Weaver model of communication, researchers came to realize that the process of communication is much more transactional in nature than the Shannon–Weaver model illustrates. Rather than communicating through a linear process, which posits one individual as a sender of a communication message and another as a receiver, a transactional model of communication accounts for all participants as senders/receivers in a simultaneous and fluid exchange. The quality of this exchange depends on the ability and willingness of communicators to gather necessary information and disseminate in an appropriate manner for the target audience. While one individual is speaking, the other communicator is providing simultaneous feedback through nonverbal cues, relational history, and the setting of the communication exchange. People constantly shape their communication patterns based on real-time events in the communication environment.

While the linear model of communication gives limited power to the receiver of the message, the transactional model equalizes their role, as communication can only take place when the two meet on an agreed-upon meaning. In the example above, the subtle Facebook message causes miscommunication between the sender and the receiver of the message. However, you don’t just examine Facebook wall posts as a singular communication process. You consider the relational history with the person who constructs them, the time of day that the message was posted, and the technology through which the message was constructed. Maybe you see that the message was posted through your friend’s new iPhone and assume that the autocorrect spelling function of the new technology made the message unreadable. Each of these pieces of information influence how you interpret the message and are just as vital to the communication process as your friend’s intended meaning. Regardless of the communication process, whether it be communication between two friends, a public address in front of hundreds, or a 140-character tweet, the better message can account for this gathering and dissemination process, the more effective the message becomes. Through this transactional lens, a more inclusive view of communication studies emerges. This leads us to our first action plan for social media communication strategists. Each will include a similar action plan to help you apply concepts to real-life marketing strategies.

References

- Shannon, 1948. Reproduced with permission of The Bell System Technical Journal

- Howard, S. (2012) The changing face of strategic communication

- Jenkins, H. (2006) Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.